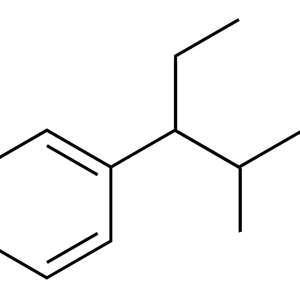

Opiates and opioids are opioid receptor agonists. The alkaloids of the opium poppy Papaver somniferum are morphine, codeine, thebaine, oripavine, etc. They are called opiates. The acetylation of alkaloids produces the semi-synthetic opiates diacetylmorphine (heroin), 6-monoacetylmorphine, and acetylcodeine. Agonists with a different structure (peptides, heterocyclic compounds) belong to opioids. Among them, synthetic derivatives (fentanyl derivatives, methadone, tramadol, etc.) and neuropeptides (endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins) are distinguished. The term “opioid receptors” comes from the name of their natural opioid agonists, neuropeptides.

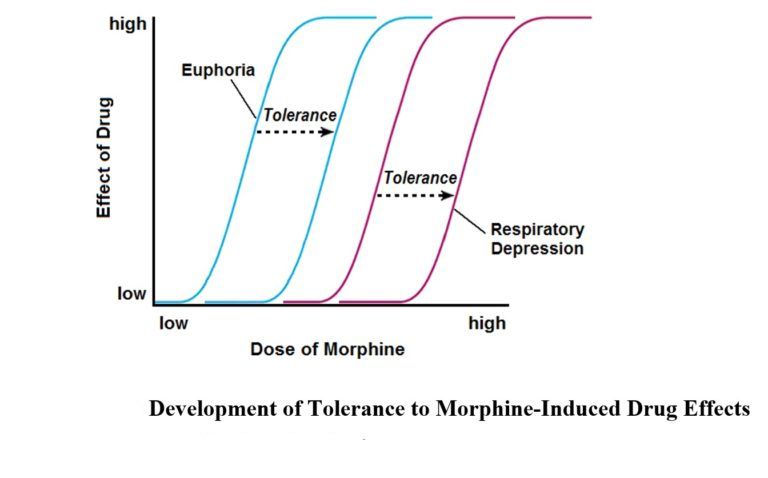

With prolonged exposure to these agents, a state of tolerance is formed, which is understood as a weakening of the analgesic effect of opiates/opioids, their euphoric and sedative effects, and their effect on a number of physiological processes, especially on body temperature regulation and respiratory function. The terms “tolerance” and “sensitivity” have the opposite meaning. Tolerance (Latin: tolerantia, the ability to endure, patience; syn. tolerance) can be defined as the body’s ability to tolerate the effects of a certain medicinal substance or poison without developing a corresponding therapeutic or toxic effect. Sensitivity is the ability of an organism, its systems, organs, or tissues to respond to the effects of a given substance.

In the context of opiate addiction, tolerance means a decrease in the reactions of the whole organism in response to repeated administration of opiates/opioids. The result of the development of tolerance is a gradual increase in the dose of the drug in order to achieve the desired effect. For example, when opioid dependence develops, the daily dose can increase tenfold.

It turned out that the rate of tolerance development is largely determined by the nature of the concomitant personality disorder, and that tolerance undergoes significant changes during the process of chronic anesthesia. For example, resistance to the toxic effects of opiates/opioids may decrease significantly after detoxification or during remission. Prolonged, long-term anesthesia is often accompanied by a gradual decrease in tolerance. This explains why fatal heroin overdoses are more common in adult drug users with a long history of illness. The rate of development of tolerance to the various effects of heroin varies. Resistance to the euphoric and antinociceptive effects of the drug increases faster in comparison with an increase in tolerance to respiratory depression. A similar discrepancy can be represented in the form of curves of increase in the values of toxic doses (i.e., doses that cause the necessary narcotic effect) and lethal doses of opiates/opioids. It can be seen that in the process of anesthesia, the difference between the values of the doses under consideration decreases. The result of the convergence of the two indicators is an increased risk of overdose in people with a long history of illness.

The reasons for the formation of tolerance are changes in the targets of opiates/opioids, primarily opioidergic neurotransmission and associated neurotransmitter systems. We are talking about multilevel rearrangements of the synthesis, accumulation and exocytosis of neurotransmitters, neuromodulators and neurohormones, receptors interacting with them, transduction systems and genes. Such shifts are often combined into the concept of “the mechanism of cellular tolerance.”

Opioidergic mechanisms of tolerance

As is known, chronic anesthesia is accompanied by impaired synaptic transmission of many neurotransmitter systems, primarily opioidergic ones. A sufficient amount of information has been accumulated on the synthesis, exocytosis, and degradation of opioid neuropeptides under similar conditions. The processes of synaptic signal transmission, including the levels of intracellular transductor systems and the genome, have been studied in no less detail.

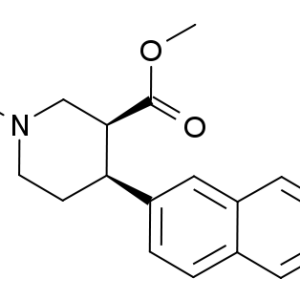

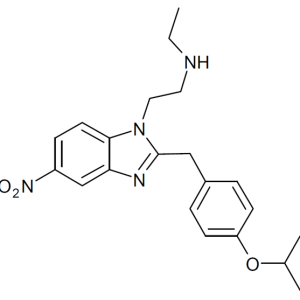

The greatest attention is paid to changes in opioid receptors during the period of tolerance formation. As is known, prolonged exposure to an agonist is accompanied by a decrease in the number of target receptors – down regulation. Ex vivo studies of chronic anesthesia in this regard often give contradictory results. A number of studies have established a decrease in the density of opioid receptors after prolonged exposure to agonists (down regulation), while other publications show the opposite effect – an increase in the number of receptors (up regulation). The phenomenon of down regulation is most consistently achieved with chronic exposure to opiates/opioids in in vitro experiments. There is also an ambiguous opinion about which type of opioid receptors (mu, delta, kappa) is involved in the formation of tolerance. All three types of receptors are probably involved, but the mu and delta receptors are the most studied in this regard. As evidence, the results of the assessment of the formation of tolerance in animals deprived of a gene for a particular receptor are presented. Thus, mutant mice without the delta-1 and delta-2 receptor genes did not develop tolerance to the analgesic effects of morphine. The role of kappa receptors in this phenomenon is less clear. The ability of kappa receptor agonists to weaken tolerance to morphine is known. It is assumed that this effect is mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.

It is generally recognized that prolonged exposure to opioid agonists reduces the sensitivity of receptors to subsequent exposure (desensitization). This phenomenon is based on phosphorylation of amino acid residues of serine and/or threonine in the region of the third intracellular loop and the intracellular carboxyl terminal (CO terminal or C terminal). The C-terminal seems to be crucial in the phenomenon under consideration. Phosphorylation is catalyzed by protein kinases related to secondary messenger systems (Ca2+ – calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, protein kinases A and C), as well as kinases associated with the G-protein receptor complex (GRKs – G-protein receptor kinases), tyrosine kinase, etc. . There is a selectivity of protein kinases with respect to phosphorylated amino acid residues. For example, the serine-266 residue of the third intracellular loop of the rat mu receptor is a target for Ca2+ – calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (in the human mu receptor, the corresponding serine is located at position “268″). Threonine-353 CO-terminals of the delta receptor and serine-375 mu receptor are for GRK.

The largest number of protein kinase targets is located in the CO-terminal region. In the mouse delta receptor, the intracellular C-tail contains seven serine and threonine residues: serine-344 and 363; threonine-335, 352, 353, 358 and 361. Upon activation of receptors expressed in HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney) cells, the DPDPE ([D-Pen2,Pen5]enkephalin) agonist phosphorylated serine-363 and threonine-358 the fastest. Threonine-361 most likely acts as a binding site for some kinase and does not undergo phosphorylation itself. The CO terminal of the rat mu receptor at the threonine-354 – threonine-394 site contains 12 threonine and serine residues, which are considered as possible sites for phosphorylation. The most “active” zone is from serine-363 to serine-375.

The phosphorylated receptor binds to the protein arrestin, cleaves from the G protein and undergoes internalization (endocytosis, sequestration) into special recesses of the cell membrane covered with the protein clathrin. They form primary (early) endosomes, in the acidic internal environment of which the initial state of the opioid receptor is restored by dephosphorylation and ligand cleavage. The process is completed by embedding the receptor into the cell membrane (recycling) and restoring its functional activity (resensitization). Some of the receptors immobilized in primary endosomes can be transported to lysosomes for final degradation.

It is advisable to differentiate the terms related to this problem. Thus, the phenomenon of down regulation can be described as a decrease in the density of neuroreceptors on the pre- and postsynaptic membrane. Methodically, this condition can be detected using radioligand analysis or radioautography. Internalization is the process of moving a receptor molecule from the cytoplasmic membrane into the cytosol. Visualization of internalization is achieved using immunocytochemical methods. Internalization is the most characteristic reaction of mu and delta receptors in response to agonist action. This reaction is less typical for kappa receptors. For example, etorphine, a non-selective agonist for opioid receptors of all types, caused rapid internalization of mouse delta receptors cloned in HEK-293 cells. Such effects were not detected on kappa receptors even at saturating concentrations of the agonist.

Desensitization is a weakening of opioidergic neurotransmission. Behavioral equivalents of desensitization could be considered a decrease in the analgesic, euphoric and other pharmacological activity of opiates/opioids, which, in fact, is similar to the signs of tolerance discussed above. The neurochemical correlate of desensitization is the weakening of the effects of opioid agonists on receptor-regulated transductor systems (cyclic nucleotides, ion channels, etc.), followed by a reduction in the cellular response. However, the initial link in this process is phosphorylation and disruption of the interaction of the receptor with the G protein (uncoupling), which, in turn, is initiated by the attachment of the arrestin protein to the receptor. It is not entirely correct to consider a decrease in receptor density (down regulation) and internalization as equivalents of desensitization. It is more appropriate to say that desensitization can be accompanied by both phenomena, although these events often do not coincide in time.

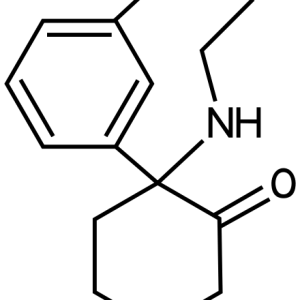

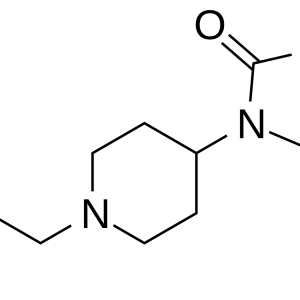

Experiments on cloned opioid receptors show that the development of desensitization depends on many factors: the cellular system used, the chemical structure of agonists, the duration of incubation, the properties of the receptor itself, including the nature of the mutation, etc. For example, morphine and levorphanol, which have a high addictive potential, did not desensitize mu receptors cloned in HEK-293 cells. Under similar conditions, methadone and buprenorphine caused desensitization. The authors attribute this phenomenon to the clinical efficacy of methadone and buprenorphine used in the treatment of opiate addiction.

The relationship between the processes of phosphorylation, desensitization, density reduction, and internalization of opioid receptors

An attempt has been made to establish links between the processes of phosphorylation and internalization. Mutant delta receptors devoid of amino acid residues, the intended targets for protein kinases, were used. The effect of agonists on such receptors was not accompanied by their internalization. It has been suggested that there may be a connection between phosphorylation of the receptor excited by the agonist and its internalization. It should be clarified that delta receptors were expressed in CHO cells (Chinese hamster ovary) and in neuroblastoma cells (NG108-15 glioma).

In the process of further development of the problem, clarifying and sometimes contradictory facts began to appear. So, S.M.Murray et al. It has been established that internalization of the delta receptor does not necessarily have to be preceded by phosphorylation. In their study, mouse delta receptors were expressed in HEK-293 cells. Mutant forms were created, devoid of possible phosphorylation sites in the CO terminal region. Exposure to the agonists etorphine and DDLE ([D-Ala2,D-Leu5]enkephalin) was accompanied by internalization of both wild-type and mutant receptors. This allowed the authors to question the crucial role of phosphorylation for subsequent internalization. In addition, in their opinion, when interpreting such results, the characteristics of the cellular system in which the receptors are expressed should be taken into account.

Y.Pak et al. It was found that the decrease in mu receptor density caused by the DAMGO agonist ([D-Ala2,N-methyl-Phe4,Gly5-ol]enkephalin) is regulated by two different cellular transduction pathways. The first is coupled to the G protein and its associated kinases (GRKs). The second pathway is G-protein-independent. Phosphorylation of the receptor by tyrosine kinase plays a crucial role in it.

Basal phosphorylation of serine-363 and threonine-370 was demonstrated on rat mu receptors (cloned in HEK-293 cells) (i.e., in the absence of an agonist). The DAMGO agonist induced phosphorylation of the threonine residue at position 370 and serine-375. The Serine 375 Alanine* mutation was accompanied by a decrease in the rate and magnitude of receptor internalization under the action of DAMGO, while the mutations Serine 363 Alanine and Threonine 370 Alanine led to opposite effects. This means that phosphorylation can not only initiate receptor endocytosis, but also counteract it. In this study, internalization was established after switching off all three amino acids from phosphorylation processes (mutation with replacement by alanine). Consequently, the fact that not only phosphorylation, but also other mechanisms are involved in internalization has been confirmed.

It is assumed that internalization is preceded by the process of transition from the dimeric form of the opioid receptor to the monomeric one. It has been established that delta receptors expressed in CHO cells are predominantly in the form of dimers. When the agonists DAPPLE, DSLET ([D-Ser2]Leu-enkephalin-Thr), DPDPE, and etorphine were introduced into the incubation medium, the process of dimer monomerization was noted, which preceded the internalization of receptors. Morphine has not been shown to have such effects. This study shows the crucial role of the terminal region of 15 amino acids of the CO terminal in the processes of monomerization and internalization of the delta receptor. A decrease in the content of mu receptor dimers in mice (expressed in HEK-293 cells) was observed when exposed to the DAMGO agonist.

It is believed that opioid receptors of various classes are capable of forming heterodimers. Such data were obtained for mu and delta receptors. With chronic morphine exposure, a selective increase in the density of delta receptors is detected, which changes the state of the mu-delta complex, ultimately leading to a violation of opioidergic neurotransmission during the development of tolerance.

There are certain difficulties in trying to draw parallels between tolerance, desensitization and internalization processes, and intramolecular events following agonist binding to the receptor (activation of G protein and secondary messenger systems, phosphorylation). The fact is that information on this problem is accumulated mainly through in vitro experiments in which cloned receptors serve as targets of agonists. It can be assumed that extrapolating the obtained results to more complex biological systems is very problematic.

Cloning of opioid receptors deprived of part of the CO terminal, as well as mutations of individual amino acid residues of the receptor molecule, alter the rate of desensitization and internalization. The effect of the DDLE agonist on the delta receptor, deprived of the last seven amino acids, was accompanied by rapid internalization. At the same time, mutants without 15 or 37 amino acid residues underwent slow internalization under similar experimental conditions. It has been suggested that serine and threonine residues play a crucial role between threonine-335 and glycine-365 in the intracellular tail. Point mutations of Serine 344 Glycine, Threonine 352 Alanine, Threonine 353 Alanine, Threonine 358 Alanine and Serine 363 Alanine fully confirmed this assumption.

Replacement of threonine-394 of the CO-terminal of the rat mu receptor with alanine inhibited desensitization. But at the same time, it turned out that mutant Threonine 394 Alanine receptors, during prolonged exposure to the DAMGO agonist, underwent significantly faster down regulation, internalization, and resensitization compared with the “wild type”. V.Segredo et al. It has been shown that the mutant mu receptor, devoid of the carboxyl tail from threonine-354, undergoes internalization even without prior agonist exposure.

In the delta receptor, one of these “key” amino acids is threonine-353, which also belongs to the CO terminal. The Threonine 353 Alanine mutation completely prevented internalization after exposure to the DADLE agonist. In the same study, it was found that serine-344, which is the target of protein kinase C, does not participate in the development of internalization. At the same time, the role of protein kinase C in initiating the processes of density reduction and internalization of delta receptors has been proven previously. Apparently, protein kinase C has several targets in the terminal tail region, each of which plays a strictly defined role.

There is increasing evidence that there is a relative independence of the processes of phosphorylation, desensitization, density reduction, internalization and resensitization. N.Trapaidze et al. No significant effect of modulators of protein kinases A and C, as well as phosphatases, on the basal internalization of mouse delta receptors (the so-called constitutional internalization in the absence of an agonist) was found. A similar result was obtained in the presence of DUDLE. In the work, desensitization of mu receptors (cloned in CHO cells) was induced even after replacement of all threonine and serine residues in the third intracellular loop and in the CO terminal.

Two closely related phenomena are also quite independent: down regulation, the disappearance of receptors from the surface of the cell membrane, and internalization, the movement of a glycoprotein molecule inside the cell. The same can be said about the effect of G proteins on reducing receptor density and internalization. Activation of G proteins is a necessary condition for opioidergic transmission. However, it turned out that the development of the down regulation phenomenon occurs both with and without G-protein excitation.

One of the possible explanations for the contradictions listed above is the parallel course of the events described. For example, slow desensitization, which does not coincide in time with phosphorylation, decreased receptor density, and endocytosis, can be explained by the simultaneous restoration of the active receptor pool through recycling, that is, by returning receptors from the cytosol to the cell membrane. In the study, mu receptors were cloned in human neuroblastoma SHSY5Y cells. The DAMGO agonist initiated rapid phosphorylation of the receptors, while the development of desensitization was delayed. However, this discrepancy disappeared after the blockade of the recycling processes.

The uniqueness of mu and delta receptors lies in the fact that in some cellular models, agonists with different structures initiate different reactions. Exposure to peptides DAMGO (mu-agonist), DAPPLE (delta-agonist) and the morphine-like compound etorphine (non-selective mu-, delta-agonist) This was accompanied by a rapid decrease in the density of receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells. Morphine did not have this effect. Morphine also did not initiate the phenomenon of down regulation of delta receptors in another cellular system, neuroblastoma-glioma NG108-15, and was significantly inferior to DAMGO and methadone in its ability to cause internalization of mu receptors (experiments on rat hippocampal neurons).

Tolerance caused by morphine

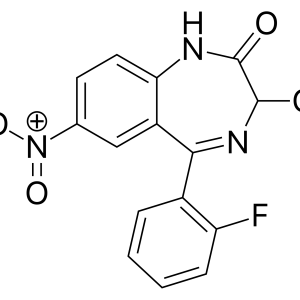

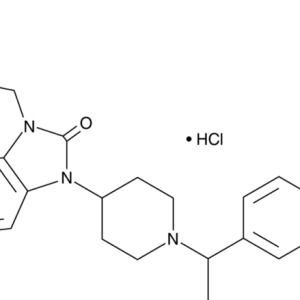

What features of the considered stages of synaptic transmission may be related to tolerance caused by opioid receptor agonists? First of all, tolerance caused by morphine, the main metabolite of heroin. There are features of the interaction of peptide agonists with the binding zone of the opioid receptor in comparison with alkaloids, including morphine.

The opioid receptor ligand reception zone is conventionally divided into areas of selectivity and a binding pocket. The former are located mainly above the outer surface of the membrane and are formed by amino acid residues of extracellular loops and tips of transmembrane domains. The binding pocket is located below the outer surface of the membrane. It is formed by spiral loops of transmembrane domains. Ligand peptides interact with both the selectivity sites and the binding pocket. Alkaloids (morphine, ethorphine) and antagonists naloxone and naltrexone bind mainly in the pocket area. In this case, the charged nitrogen of the ligand molecule is able to interact with the residues of aromatic amino acids of the polypeptide chain.

There is an obvious pattern: peptide agonists, which are inferior to morphine in their ability to initiate tolerance, have special sites of specific binding. But, on the other hand, etorphine interacts with a similar region of the morphine receptor. However, the formation of tolerance under the effects of etorphine is slow.

Morphine binding is accompanied by inhibition of adenylate cyclase with the involvement of G protein. A similar mechanism is characteristic of other opioid agonists. However, unlike peptide agonists and etorphine, morphine weakly activates the phosphorylation of opioid receptors. It is assumed that morphine stabilizes the mu receptor in a conformation in which phosphorylation involving protein kinases associated with the G-protein receptor complex (GRKs) becomes impossible. It is possible that there are several conformations of the excited opioid receptor depending on the structure of the agonist. The nature of the conformational rearrangement determines the possibility and effectiveness of the interaction of the receptor with protein kinases. In in vitro experiments, overexpression of a protein kinase associated with the G-protein receptor complex has enhanced the ability of morphine to initiate the processes of phosphorylation and internalization of mu receptors. Ex vivo experiments revealed an increase in the expression of the protein protein kinase GRK in the blue spot of rats against the background of chronic morphinization. This fact can be considered as an adaptive response of neurons to excessive drug exposure. Similarly, an increase in the content of the GRK2 kinase in the frontal cortex of heroin addicts who died of an overdose can be explained.

The subsequent events initiated by morphine are also significantly different: it does not cause pronounced desensitization, decreased density and internalization of opioid receptors.

An analysis of the above suggests that morphine acts differently from other agonists even at the earliest stages of opioidergic neurotransmission. Such differences create the conditions for the emergence of tolerance. Gradually, an opinion was formed about the possibility of influencing the process of drug binding to the receptor and about the possibility of changing the course of subsequent events. The first step in this direction was the assessment of tolerance in the mode of combined administration of morphine and opioid receptor antagonists naloxone, naltrexone and nalmefene. Under such conditions, the rate of drug tolerance significantly decreased (estimated by analgesic effect). Consequently, theoretical developments have become a prerequisite for the development of a new clinical direction – optimizing the use of morphine for the treatment of pain.

Morphine activation of the opioid receptor is not accompanied by binding of the receptor to the protein arrestin for subsequent sequestration into the cell. Most likely, this phenomenon is a consequence of the drug’s inability to initiate phosphorylation. As proof, we present the results of the work. Mu receptors, protein kinase associated with the G-protein receptor complex (GRK), and arrestin were co-expressed in HEK-293 cells. Morphine caused internalization of receptors with overexpression of protein kinase and arrestin (its content in the cell increased by 30 or more times). This effect disappeared if the phosphorylation step was blocked.

Dissociation of the receptor-G protein complex is necessary for desensitization of opioid receptors after exposure to an agonist. If we ignore a number of contradictions in the description of events following the excitation of the opioid receptor (see above) and follow the “classical” concepts, we can say that dissociation of the nerve ending and G-protein is possible only when the receptor is phosphorylated and the protein arrestin is attached to it. As discussed earlier, these processes are not characteristic of the action of morphine. When the protein kinase GRK and arrestin were overexpressed, it was possible to achieve desensitization of the mu receptor with the help of a drug.

The role of beta-arrestin-2 in the formation of tolerance to the analgesic effect of morphine was evaluated in mice lacking the gene for this protein. The animals received the drug at a dose of 10 mg / kg of body weight per day for 9 days. Using the hot plate test, it was found that there were no changes in the analgesic effect of the opiate. In the control group of wild-type mice, tolerance developed progressively during anesthesia. In a parallel series of experiments, the effect of the mu-agonist DAMGO on the specific binding of 35S-guanosine triphosphate to the synaptic membranes of the brain stem of rodents in the experimental and control groups was evaluated (this approach allowed us to assess the state of the opioid receptor- G protein system). By the end of 5 days in control mice, the agonist had no effect on the binding parameters of 35S-guanosine triphosphate (development of desensitization). In mutant mice, the parameters of the radioligand study under the influence of chronic anesthesia did not change in comparison with the initial data (absence of desensitization). Thus, the role of beta-arrestin-2 in the formation of desensitization and tolerance under chronic morphine exposure has been proven in in vitro and ex vivo experiments.

The intracellular carboxyl tail of the mu receptor plays a crucial role in inhibiting the processes of phosphorylation, desensitization, internalization, and resensitization observed when exposed to morphine. The most significant site is the final amino acid sequence, starting from leucine-387. Splice variants were created that differed sharply from the “wild” type receptor precisely in the polypeptide chain from position “387”. When morphine was applied to some of these mutants, phosphorylation, desensitization, internalization, and resensitization were detected, which was not observed when the drug activated “wild” type receptors.

A paradoxical situation arises: high-affinity agonists, which have the ability to activate the opioid receptor, trigger the processes of phosphorylation, desensitization, density reduction, internalization and resensitization, are significantly inferior to morphine in terms of tolerance formation. The cell includes adaptive mechanisms (desensitization and internalization) to prevent further agonist action. In this case, the probability of modulation of a number of intracellular biochemical pathways, including gene expression, decreases. Morphine may take longer to act in this regard, as the protective mechanisms of the receptor-level cell are less effective. There is an opportunity for profound changes in the structural and metabolic complexes of the cell (providing energy exchange, plastic processes, the function of membranes and ion channels, storage of genetic information, etc.). Consequently, the development of tolerance under the influence of opioid peptides, etorphine and other agonists can be represented as a process directed from the outside into the cell, while morphine induces tolerance coming from the inside, as it were, from the genome. While the first type of resistance is more or less clear and structured (opioid receptor activation, phosphorylation, desensitization, internalization), the second is much more complex and involves the modulation of not only opioidergic systems (both directly and through changes in gene expression), but also other neurotransmitters and many biochemical processes in the cell. These shifts may form the neurochemical basis of morphine-induced tolerance.

The following chain of events is assumed. Activation of opioid receptors induces cascades of intracellular transducers (cyclase, phosphoinositide, calcium, etc.). Secondary messengers through the protein kinase system affect the transcription of “early” genes – c-fos, fos-B, c-Jun, Jun-B, Jun-D, Fra-1, Fra-2, Krox-20, Krox-24, etc.. Proteins Fos, Jun, CREB, etc. are expressed, which are capable of forming homo- and heterodimers. Dimers bind to specific DNA regions in the promoter regions of many “late” genes and regulate their transcription. Opiates/opioids are associated with “early” genes primarily through the cyclase system. For example, cyclic adenosine monophosphate affects DNA through the “early” CREB gene and the corresponding ssCRE-BP (single-stranded cyclic AMP response element-binding protein) protein. Prolonged opiate/opioid anesthesia alters the activity of this system. It has been shown that the nuclear factor ssCRE-BP is a polypeptide with a molecular weight of 110-150 kDa. It includes two domains containing a significant number of glycine and glutamine residues. The mRNA encoding the studied protein has also been isolated.

Such theoretical considerations would not go beyond the scope of an ordinary scientific discussion if two unfavorable side effects of the analgesic morphine were not known: a high addictive potential and the ability to quickly form tolerance. If we assume that the development of desensitization and internalization of receptors is a normal adaptive reaction of the cell under the excessive action of opioid agonists, then the recycling and resensitization of opioid nerve endings following the listed events return the cell to its original state. In addition, blocking the transduction signal caused by the excitation of the opioid receptor reduces the likelihood of subsequent intracellular reactions. First of all, this applies to maintaining the equilibrium of the main structural and metabolic complexes of the cell, including gene expression. Morphine, which can excite opioid receptors and activate secondary transmitter systems, does not form a “feedback loop” to prevent excessive effects on the target cell. The processes of phosphorylation, desensitization, and internalization are slowed down. This means that the effect of the drug will be more “profound” and may reach the level of gene expression. Tolerance in this case can be determined not only by changes in various parts of opioidergic systems, but also by serious shifts in associated neurotransmitters, ion channels, cell membranes, plastic processes, energy exchange, etc. The direct initiator of these deviations is not excessive activation of the receptor agonist, but a violation of gene expression.

Thus, with prolonged exposure to opiates/opioids, the processes of desensitization and internalization of opioid receptors develop. Such a reaction can be considered as part of an adaptive restructuring that protects the cell from excessive exposure to a pharmacological agent. Under the action of morphine, desensitization and internalization are slowed down, which creates conditions for excessive activation of transductor systems and gene expression. Transcription-level disorders may form the basis of tolerance in chronic drug exposures.